The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics measures all kinds of things about our working lives — the unemployment rate, our average hourly earnings, even our productivity.

But one thing the BLS doesn’t try to measure is how many times people change careers in their lives. The reason is because it’s just too hard to define a career change. Is it any time you change employers? What about if you stay at the same employer, but move into a different position? Or if you change jobs, and then switch back — is that two career changes or just one?

But I recently met two men in the Buckeye neighborhood who have absolutely, in no uncertain times, changed careers. Even the BLS would recognize it.

The first is a barber who’s becoming a lawyer. The second is a computer scientist who’s becoming a grocer.

First up, Demetrius Williams, the owner of Ambitions Barbershop on the corner of East 117th and Buckeye Road. I actually approached Demetrius not to talk about his job, but for a really different reason. A lot of people I’ve talked to in the Buckeye neighborhood over the years have told me they feel like the street corner right outside is a haven for young men dealing drugs. I wanted to ask Demetrius if those perceptions were correct.

We talked about that — but before we get there, he also told me about his own career path. And how it’s connected to what he hopes to do for his neighborhood.

Here’s Demetrius Williams, in his own words.

Demetrius Williams, Barber/Almost-Lawyer

I live in Mount Pleasant area, I've been there about the last four years. Right now I'm standing on 117th and Buckeye in front of my barbershop.

I’ve been here since 2003. I was just a barber then. And then in - what was it, 2006? - the gentleman that owned the barber shop wanted to get out of the business, so he sold it to me.

The name of my shop is Ambitions Barbershop. The name comes from my ambition, my drive or whatever, and I'm ambitious about a lot of things, so I just put the ‘S’ on the end cause I have multiple ambitions.

Four years ago, I'm approaching 40, and it's like, ‘Okay, I'm not going to be 45 - I mean, there’s nothing wrong with it, don’t get me wrong - but I'm not gonna be 45 or 50 cutting hair.’ Or at least that's my only occupation.

I just always wanted more, I always need more. I was a barber, and I ended up owning the shop and now it’s like, "What's next?” So I went back to school, because I decided I wanted to be a lawyer.

Well, I didn't decide. I mean, that's what I wanted to do since I was a kid. I went back to actually attain that goal.

It was rough! You know, you're an adult now, you’ve lived this life, you've established a career. You're well past that youth, [where] you’re fresh out of high school and you're used to doing work and you’re used to going back to school after the summer and giving up your life for school.

So I went back, finished my bachelor's and then immediately applied to law school. I just graduated last May, or this May should I say. So I’m studying for the bar exam in February, and then that's my next move, pass the bar exam and start my own practice.

I may start my practice, and still cut hair on the weekends. I love it, so I may very well do that.

I do talk to people regarding the law. I mean, to the extent I can. I'm not an attorney, so I can't give legal advice, but I can point you to where you need to go. Either to find the exact information or where to go file whatever it is you need to file.

I hear about these community meetings and things. They say, ‘Oh you let guys run in and out of your shop selling drugs.’ It's like no, anyone in this neighborhood knows, you can't sell anything in here. You can't sell drugs, let me say that.

Don't get me wrong. You can catch a guy stop here and doing something wrong. But it has nothing to do with me.

It bothers me because you have individuals that, they don't have a horse in the race, other than just to speak negativity. They're not there observing what's really going on, they don't know who's coming in and out. And then they themselves do nothing with these youth, they make no effort to speak to them to do anything for them. They do nothing for them, but there's always this chatter: ‘They're standing on the corner.’

I hope the most for this neighborhood that these young men - the young men and ladies but more so the young men because those are the ones we see go astray - I just hope that they grow to be the best that they can be, not allow any negativity to bring them down, anything that may distract them, or stop them from growing in the way they need to grow.

I would love to see something in this area, that was some sort of, not necessarily a school, but just just a resource, some sort of place they can go. And if you have a resume, you wanna apply for jobs, you don't have computers at home, you have no idea how to write a resume somebody can help you with it. So I would love something where we could get resources out to the community.

My name is Demetrius Williams. I'm a barber, and I also have my JD. I don't think there are many of us.

#

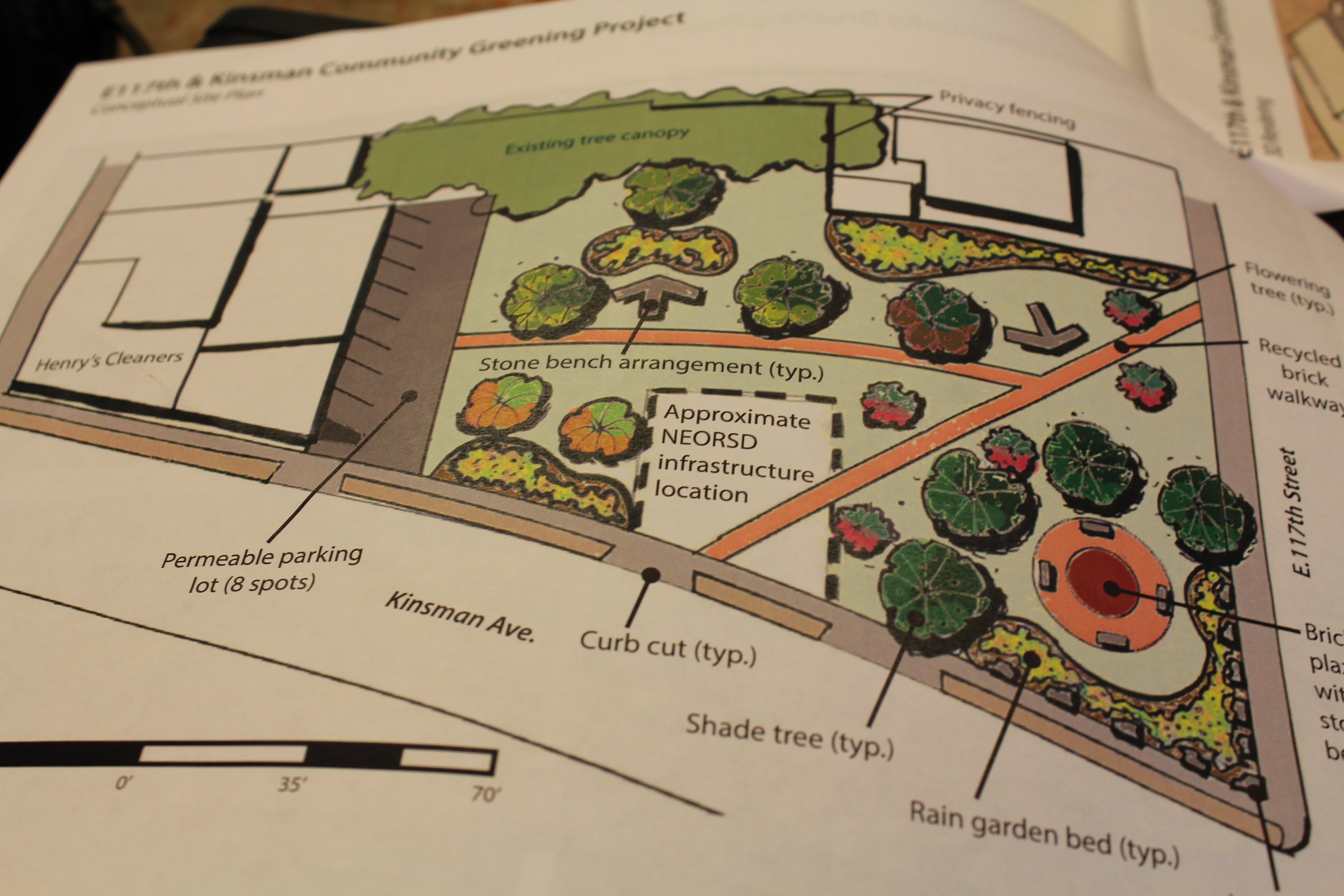

If you follow this podcast, or the Buckeye neighborhood in general, you probably heard about how the supermarket chain Giant Eagle closed its location on Buckeye Road about a year and a half ago. We featured the story in our episode from last year, Two Years and Change.

Anyway, when the store left the neighborhood, it left a giant hole — not just a physical one, but an emotional one, too.

Well, there’s some good news on that front. A new supermarket just opened in the old space, and it’s run by a local operator called Simon’s Supermarket. It’s Simon’s fourth location, following others that already operate in Fairfax and the inner-ring suburb of Euclid.

Fahmeed Afzal is the manager of the new Buckeye store. He emigrated from Pakistan to New York City in 2005, studied and taught computer science at Long Island University, and wrote a master’s thesis about something called “probablistic relational databases” that I won’t even try to understand.

He tells me about his path to Cleveland and the grocery business, and also why his store can be successful in a neighborhood where a larger chain couldn’t. Here’s the interview.

Fahmeed Afzal, Computer Scientist/Grocer

JG: So I got a chance to walk around a little bit before we sat down. And the store is huge.

FA: Yes.

JG: You’ve got aisles and aisles, a big produce section with lots of fruits and vegetables. How many square feet is it altogether? And is it challenging to fill all that space?

FA: Ah this store is actually one of the biggest stores, so far, that we own. And the square footage is 60,000 square feet, which is huge for our size of business. From an aisles point of view, actually, what we did, we brought in (clears throat) a huge range of household items which include your kitchen, bed, bath, rugs, toys, and some hardware.

At the same time, we brought a good selection of Asian products which we have seen a very exciting response from customers, not only the Asian customer even the local customer. To my surprise, they already aware of these products, I don’t know. And they were so excited to find them here.

JG: Yeah, yeah, I noticed you got a whole isle of Asian products which is cool. How did that come about?

FA: I live here, Shaker Heights, which is like not even a mile away from this location. So I see, in the neighborhood there are a lot of Asian community over there. So from that, I got the idea, like we should not be limiting this location just for regular grocery. We should make it a concept of like an international store.

JG: And this is also a predominantly African-American neighborhood, right around here. So can you speak to that, how you serve those customers.

FA: The first thing, like I said, this is our fourth store in a similar neighborhood, so this is not new to us, we are very well aware of all the business needs. We know our customers very well, and we are very close to their needs. So the first thing is, we have a very clear direction from the business, we just go with the brand name grocery with best or affordable prices. Our best seller in all our locations is our meat like we have 40% of the sales of our meat 10% of the fresh produce.

JG: So 40% of your total sales are meat and 10% of your total sales are produce, and the rest is canned goods, and dry goods?

FA: And frozen and everything else.

JG: So this was a Giant Eagle store up until 2017 when they closed. Why do you think they closed? And then, what's gonna make Simon’s successful that they didn't do?

FA: So, I don't have any documentary proof, but I heard that they were having a $1.4 million dollar loss reported yearly. But yes, going back to why they were not successful here, and why they closed. I think in the beginning I noticed a corporate kind of set up where it is a huge hierarchy, And then the main factor that we noticed the Giant Eagle is not, I think, equipped enough to run a business in the inner city. I think this is the only location where they tried that inner city model. Most of their stores are, like, suburban. We were running three stores successfully in the inner city, so we know what are the challenges and the solutions to those challenges in inner city.

JG: And I'm sure that this is a complicated question, but what are some of those challenges and what are the solutions?

FA: Just, I think in the beginning, as I said, like we are very close to our customers, based on the management and decision making, which I believe I’m not much aware, or familiar with that, but my understanding is probably Giant Eagle was not like that, since it’s just the managers who are just limited with their decision-making.

JG: The trend, especially in lower income neighborhoods, communities of color, and rural communities, is that big supermarkets are closing and new ones are not opening up. I was seeing some statistics online, that of the 2,400 new grocery stores that opened between 2011 and 2015, only about 250 of them were in “food deserts” - or areas that don't have access to fresh produce and healthy food. So, you talked about the centralized model. Do you think that is the reason why so few large grocery stores open in low income neighborhoods, communities of color, rural neighborhoods? Are there other factors?

FA: I think the biggest factor that is missing there is, again, a team and collaborative work. When I say a collaboration, if a business is not connected to the community and if the community does not feel that this is their own store, then running that business in a low-income neighborhood becomes very difficult.

JG: Can you paint a picture for me? How does that community interaction look?

FA: Before we started the store we got, I think, a three-page letter from the community, from their different meetings when Giant Eagle was closing. And a few of them say, this store is not well-lit enough, and the quality of the grocery was not good. The customers were not treated respectfully, there was no electric carts, no motor carts for the elderly people.

So during even the construction of this project, we had all our community, city, members, leaders and the business owners had several meetings. I would say at least five meeting before we opened the store where we discussed our challenges, questions, concerns from the community, any suggestions from the city, all that. So that gives that connection. The one I was talking about. So they feel like, ‘Okay, here is someone listening to them, so someone is interacting and react to their concerns and questions.’

JG: What was the total investment in the store?

F: $2.2 million, approximately.

JG: Wow. $2.2 million, that’s a lot. That's probably more than most people think it takes to open a grocery store. And how many employees do you have?

FA: When we started the store, since it was a soft opening, we started with 50 employees. By the time we have the store running to its maximum capacity, we will be looking at probably 80 to 100 employees.

JG: So how are you feeling so far?

FA: It's a very over-whelming response from customers, when they come to store. Especially the elderly. Because I know here we have a big number of customers who are walk-in customers. So they come here, and they specially take five minutes and look for me, or some of the managers. And they pay personal thanks to us that you opened the store, [they] really needed the store here.

JG: Lastly, tell me a little bit about you. So you said you live in Shaker Heights, about a mile away. You have family over there?

FA: Yes, my family is here, and I actually moved in Ohio a year ago when we started working on this [store].

JG: Where did you live before that?

FA: I moved from New York and, by profession I'm a software engineer. Fifteen to 20 years I was in that field, and I was at one time also a professor of computer science at Long Island University in New York. But I think, I was just thinking, all that knowledge that I accumulated over that period of time, that brought me here, here just to give me a bigger scope of challenge to solve.

JG: I think it's pretty cool to have a professor will running a grocery store.

FA: (laughing) Yeah, that's very interesting. Sometimes I feel myself involved in having discussion and conversation with my employees from a different point of view, it’s not like an employee and manage relationship. I try to bring to their attention that this is not just like an employee business relation. It is direct and indirectly your own, like if the business grows, you grow.