Note: This episode was a collaboration between Watershed and ideastream, Cleveland's public media outlet. Also check out a short video version of the story.

There’s no zen-like music playing in the background, no incense burning, no stretchy yoga clothes, and it’s not at a studio or even a traditional gym. But it is a yoga class, and it’s happening at Zelma George Rec Center, in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood of Cleveland.

With the sound of the bell, about 30 or 40 kids lie down on their mats. A lot of them have just finished eating the free lunch the center provides. The neighborhoods around the rec center have some of the highest poverty rates in the region.

By the latest counts, more than half of all residents, and nearly three quarters of all children, live below the poverty line.

“What does yoga do for us? It works on our flexibility balance and strength,” said yoga teacher and Buckeye-Shaker resident Kimberly Archibald Russell. She says one reason she became a yoga teacher was to help the people around her cope with the problems that come along with poverty, which include stress and a lack of healthy food.

“Just like everyone else, I see people that are heavy, I see people that are smoking, and I just see that they need a better way of life,” she said.

In Mount Pleasant, about half of adults have high blood pressure — twice the national average. One in five report mental health problems such as depression. And these conditions aren’t unique to Mount Pleasant. In many neighborhoods where poverty rates are high, chronic physical and mental illness have become persistent problems. Some residents, like Russell, are confronting disease not just through doctors and drugs — but techniques to manage long-term stress.

“I just want folks to know there’s things they can do to help,” said Russell.

Russell teaches in two city rec centers, public schools, a community center, all within a mile or two of her house. Her company, My Village Yoga, is all about bringing her neighbors the benefits of yoga. (She also works with ZenWorks Yoga, which brings yoga to public schools.)

“Calmness, serenity, control, discipline—it’s just introducing it. That’s what I’m trying to do,” she said.

The fact that Russell lives in the neighborhood, and looks like the residents she’s teaching, helps her overcome the stereotype of who yoga is supposed to be for. “People that practice yoga aren’t necessarily white skinny females. It’s all of us,” she said.

One time, she was walking into an elementary school on the East Side, she recounts, “and a little girl who had been in my first class, said, ‘There’s my favorite yoga teacher!’ and I said ‘Oh, I’m your favorite yoga teacher even though this is only our second time meeting?’ and she said ‘Yes. You’re brown like me.’”

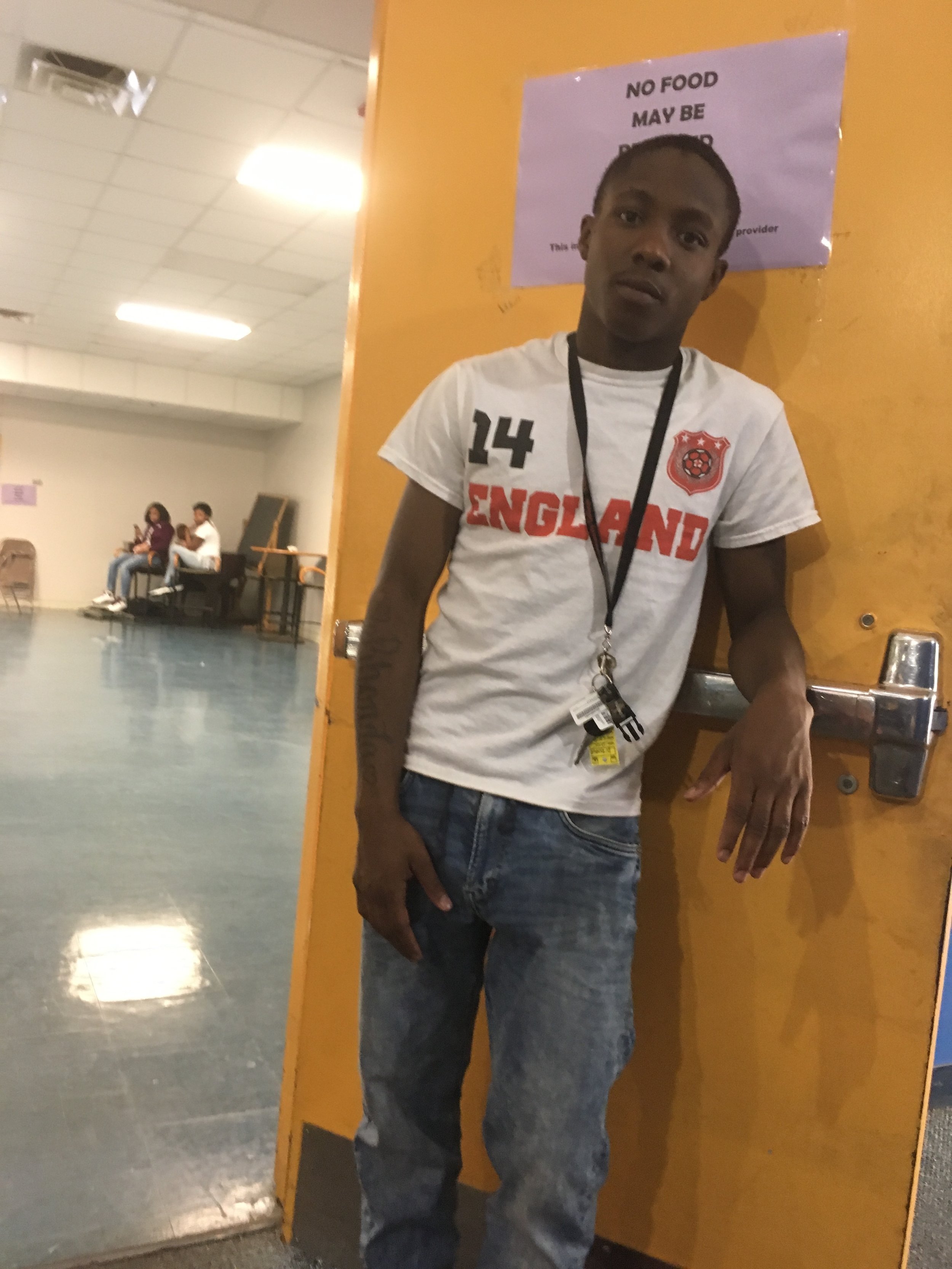

Lamont Thomas, a 20-year-old supervisor at Zelma George, says that after only a couple classes he’s already hooked on how calm he feels after taking a class. “I never did yoga before,” he said. “Subconsciously I didn’t know I was breathing slower than I was before I started. Then I started noticing I was taking deeper breaths. And that’s cool,” he said.

Another organization in the neighborhood, Fairhill Partners, also offers a range of classes to help people stay healthy.

“Zumba, Pilates, yoga, tai chi, all of those are a good fit for somebody,” said Fairhill’s director, Stephanie FallCreek.

FallCreek says hospitals and doctors are important, but they tend to focus on treating sickness rather than on maintaining health. In neighborhoods like Mount Pleasant, she said, “we have a wealth of healthcare services and a poverty of access to a certain kind of preventive and proactive self-management approaches to doing the best we can with the health that we have, and with the resources that we have.”

Which is exactly why yoga instructor Kimberly Archibald Russell says she hopes her students take what they learn back to their families.

“Oftentimes at the end of the class, I’ll say, ‘Now comes our true practice of yoga, after we roll up the mat and go home,’” Russell said.