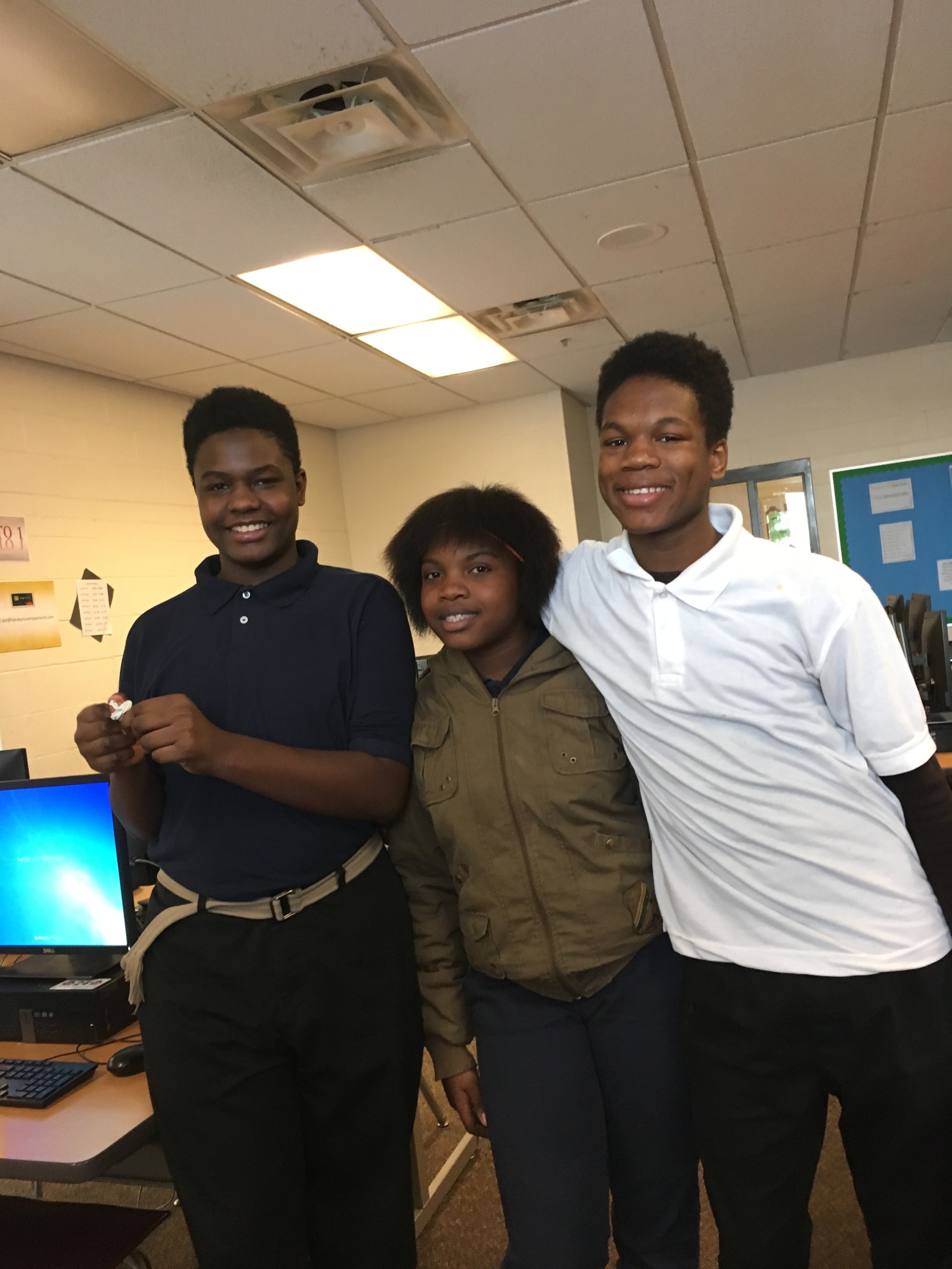

Photos 1-2 show Kiara (center) and Eddie (right) with their friend Linell (left). Photo 3 shows Nelson Beckford (left) and Capt. Keith Sulzer (right).

As part of my job telling stories from the Buckeye, Woodland Hills, and Mount Pleasant neighborhoods, I pay attention to how the neighborhoods are portrayed by other media.

And last year, there was one story that probably got more attention than any other. Front page news in the local media for a couple of days, even picked up by the New York Times.

It happened on the day after Thanksgiving. A 12-year-old boy was shot and killed outside his dad’s beauty supply store on Buckeye Road. The boy was from the suburbs, visiting his dad at work during his day off school, and he got caught in a spray of bullets aimed at another group of boys — boys he didn’t even know — outside the store. Five of those boys were wounded too, one critically.

The story was horrifying in itself, of course, and raised a ton of questions that we as a nation seem to grapple with more and more often lately. What could possibly drive kids to shoot at other kids? How did they get the guns?

But I also got pretty upset thinking about how for a lot of people in Northeast Ohio and beyond, this might be the one story they hear about Buckeye all year - or at least the one they remember most. And it’s one that confirms a perception that many people already have about the neighborhood - that it’s unsafe, even deadly. Maybe especially for outsiders. Like the boy who died.

In this episode, I try to provide a couple of neighborhood perspectives on this. First, I talk to a couple of kids from the neighborhood - kids who went to school with the boys who were the targets of the shooting.

Then, I meet with a police officer and a foundation program officer to talk about some of the work that’s being done to prevent violence like this in the future.

Part 1: The Kids

Unlikely friends

Eddie and Kiara are in the eighth grade at Harvey Rice K-8 School, on the border between the Woodland Hills and Buckeye neighborhoods.

They’re not boyfriend and girlfriend, and according to most stereotypes about teenagers - they probably shouldn’t even be friends. Eddie’s tall, outspoken, a jock - he’s on the school’s basketball team, which went 6 and 1 before playoffs this year. He lives in the Woodland Hills neighborhood with his aunt.

Kiara’s quieter, dressed in jeans and a plain green jacket. She likes to hang out at the library after school, and says she has trouble showing her emotions. She lives right off Buckeye Road.

The two of them meet me in the computer lab after school. They often hang out here together after classes let out - at least on days Eddie doesn’t have basketball practice.

I start out just asking how the two of them feel living in their neighborhoods - safe, not safe, or somewhere in between.

"I really feel that it isn’t a safe neighborhood over here," Eddie tells me. "It’s fun but it’s not safe. One time I was walking and someone asked me do I want to buy some marijuana from them. So I don’t feel as if it’s safe over here."

For Kiara, the answer’s a little more complicated.

"I feel safe sometimes," she says. "It depends on where I’m at."

That tracks with statistics, which show that there’s a big difference in crime rates depending on exactly where you are in the neighborhoods. According to the Cleveland Police Department, the violent crime rate in Buckeye and Woodland Hills is anywhere between being about average for the City of Cleveland overall, to being about the twice the rate of the city overall. It’s between four and seven times the national violent crime rate.

'Hood stuff' and guns

But Eddie and Kiara knew the boys who got hurt that day. And whatever the statistics say, when you know another kid who gets shot right in your neighborhood, that obviously can make a big difference in your perceptions of safety.

"I felt stunned about it - I thought it was unbelievable," says Kiara. "It’s just a bad feeling."

Eddie says when he first heard about the shooting, "I felt some type of way about it."

I ask him to elaborate.

"I felt as if guns should be taken out of children’s hands," he tells me. "Guns are used to protect you and people use them to shoot people just because they don’t like them, or over hood stuff."

“Hood stuff” - that’s Eddie’s term for rivalries between neighborhoods. Turf wars. And it’s what he and Kiara think motivated the shooting on Buckeye, at least on the surface - a group of kids from one neighborhood angry at kids from another, or just trying to show their dominance.

As for using guns to solve those disputes? Kiara says that’s a simple matter of kids modeling their behavior on what they see older people around them doing.

"It’s like if people got older cousins or their older brothers are just like addicted to the streets," she says, "they’re gonna follow after them."

She adds: "Say their uncles are selling drugs or something. They’re gonna wanna do that. They think it’s cool. If their uncle's shooting people, they’re gonna want to do it too."

The kids tell me they can empathize with how people could fall into that negative cycle. More than half the people in Buckeye and Woodland Hills, 54 percent, live below the poverty line. That's due to a lot of factors that are out of people’s control: Mortgage lending and property valuation practices that favor white neighborhoods, the outmigration of jobs to the suburbs or out of the region altogether.

For a lot of people that can create a feeling of frustration, sometimes anger.

"They're in a negative environment, and then as time goes by, when you think negative things you get negative things back," Eddie says.

Kiara says she’s felt that negativity showing up in her own behavior.

"I fight a lot," she says. "I don’t ever show my emotions, I just hold a lot of anger in and it just gets to that point where I got to solve it out with my fists."

She says she's working on talking through problems instead of getting physical.

Both Eddie and Kiara say what’s helped them stay positive, and the thing they think could help others, is positive relationships. Being around teachers and coaches - and especially other kids - who for one reason or another have chosen to steer clear of negativity themselves.

Their own friendship is a great example.

"I think what draws me and Kiara together is like, we understand each other," Eddie says. "Because before, I had an issue but I learned to control it."

A 'good character'

He says he knows what it is to feel abandoned, bullied - even to be a bully.

"The reason I was mean is because growing up, there were a lot of things missing," he says. "And the one big thing that was missing was, I felt abandoned. I don’t really like talking about it because it’s different now, but back then I was just so abandoned."

That was a few years ago, when he was at a different school. It was a persistent classmate, a girl named Maia, who was finally was able to break through.

She’d been through a lot of the same stuff and could understand where he was coming from, and that made him feel safe. Ever since he transferred to Harvey Rice in sixth grade, he says, he’s tried to be that understanding friend for other kids he sees struggling.

And he says he’s not alone in that. There are kids making friends with each other, helping each other, all over.

But people don’t hear about that. They just hear about things like the shooting on Buckeye, and they think, "'Oh, this is another incident of those black people who don't know how to act,'" he says. "They may even feel sorry for the people because they’re ruining their lives."

But he wishes disapproval or pity were not the only things people thought about when they thought about Buckeye.

"The story I would like you to tell about our neighborhood is there may be a lot of stuff going down in our neighborhood," he says. "But at the end of the day ... a lot of people around here are good people. They may make bad choices but they have a good character."

Kiara says she feels the same way. She says things like the shooting on Buckeye definitely scare her, and people should pay attention so that they can come up with solutions. But there’s also a lot of positive stuff that happens here that she wishes got more attention, too.

Things like The Soul of Buckeye Festival that happens every summer.

She wishes more people would come to events like that, so they could see a side of the neighborhood they don’t typically see in the news.

"I want them to be amazed," she says.

Part 2: A New Kind of Policing

To talk about what’s being done to build on those positives, while also dealing with crime - I meet with Nelson Beckford, now a program director with The Cleveland Foundation; and Captain Keith Sulzer of the Cleveland Police Department. You may remember Captain Sulzer from last season’s Walk With a Cop episode.

The two of them have been teaming up since 2015 to build up a community policing program in the department’s Fourth District, which includes Buckeye, Woodland Hills, and Mount Pleasant.

Nelson was a program officer at the Saint Luke’s Foundation back then, and he says he approached Captain Sulzer with the idea of "getting out and building relationships with people, [starting] that person by person cop to civilian, cop to shopkeeper, cop to block club leader conversation."

That’s pretty much the idea of community policing: that a great way to prevent crime is for police to build positive relationships with residents and business. Which of course has been especially challenging in African American neighborhoods in this country. If people trust cops more, then cops hear about problems, and can help people address them before they become crimes.

The Saint Luke’s Foundation made a grant so the police department could pay officers to do community policing.

"There’s probably 10 officers and civilians working in the unit right now," says Captain Sulzer.

He'd like to see that number grow.

"It would help the city dramatically ... to be able to get [more] policemen in the schools talking to kids walking in the community, in business districts, getting to know business owners, to know the people living there," he says.

A big part of those officers’ jobs, and how this all ties back to the shooting on Buckeye Road, is just hanging out in schools. Walking around in their uniforms, doing things like reading books to kids and taking them out for ice cream. Captain Sulzer himself has pretty much become a fixture at Harvey Rice, where kids know him by name.

"If I have nothing to do I’ll go walk around the schools," he says.

If the cops can build positive relationships now, the hope is that later, as the kids get to be teenagers, if they’re having problems or feeling unsafe or they have a friend who’s getting into drugs or guns, they’ll see cops as allies rather than adversaries. People who can help intervene before anyone gets arrested or sent to jail.

"That’s where we need to do our work," he says. "The kids need to see an officer in the school that cares about them. We’re not there to just arrest somebody, and that’s the only time they see us, when there’s a problem."

Nelson Beckford says the outcomes aren’t being measured in crime rates going down, though of course that’s an outcome everyone hopes for.

"The things we measured were positive community police interaction, [for example] the number of times police went to community events," he says. "So we were counting the positive interactions between the police and the community."

The police department counted more than 5,000 of those interactions in the 4th District in 2017 - contacts with citizens and business owners that weren’t about dealing with a particular crime but instead just checking in, building relationships.

That’s about 10 times the number as in 2016. The department will also be tracking resident perceptions of the police. In 2016, only about 56 percent of residents in the 4th District said they felt positive about the relationship between police and the community. The hope is that over time, that number gets a lot closer to the 82 percent of white people citywide who say the same thing. (Data courtesy of the Cleveland Police Department, not yet available online.)

When it comes to incidents like the shooting on Buckeye Road, Nelson and Captain Sulzer say they believe community policing can make a long term difference. But there’s also a need to work more closely with one particular population.

"Boys, in my opinion between like 12 and 17, we treat them as if they’re tough and rugged but I think they’re probably vulnerable and very, very fragile," he says. "They need positive figures to help them see there’s another way."

Of course, Kiara and Eddie talked about that same thing - young boys seeing older guys and modeling their behavior after them.

"Boys naturally want to form into cliques," he says. "It could be a baseball team, a gang, it could be kids getting together every saturday to ride bikes. We need to know that’s a fact of boys and create alternatives to those natural things that boys want."

Part 3: 'They're All Cool'

Back at Harvey Rice, I got a chance to check out Eddie’s basketball practice after we talked.

He was completely in the zone - eyes focused, barely noticing me or anyone else in the stands. He told me afterward that what he loves about playing is just that it simplifies his mind. For that time he’s on the court, nothing else matters. And even more than that, he just likes being with the other players.

"It’s just the fun of it, being on the same team as certain people," he says. "Some of them are better than me. I’m not scared to admit they’re better than me. But it’s just like, they’re all cool."

As I left Eddie for the day, I thought, that 12-year-old who was shot - that was news, of course. But this is news, too.

That this 12-year-old, who once felt friendless and abandoned and was a bully, found another way. That’s just as momentous and instructive as anything else we might hear about Buckeye Road. Maybe even more so.